Since Florida’s statehood, a frontier spirit helped form new communities. Natural disasters, new technologies, and social and economic factors also shaped the state. These forces helped many communities thrive and continue to grow, while diminishing others; leaving very little evidence that these vibrant communities and their inhabitants ever existed. From Newnansville, which is now almost completely gone, to Hastings, which is in decline, these communities reveal much about Florida history. Their rise and fall reflects broader social, economic, and political trends that still affect the entire state and will likely continue to affect us in the future.

Curated by Dr. Bridget Bihm-Manuel and Hank Young | Designed by Lourdes Santamaría-Wheeler and Katiana Bagué

This online exhibit is based on the exhibit of the same name that was presented at the University of Florida George A. Smathers Libraries from January 18, 2022 – April 8, 2022. Unless otherwise noted, all items are from the P.K. Yonge Library of Florida History, Special & Area Studies Collections, George A. Smathers Libraries.

HASTINGS, FLORIDA

Established in 1890 to provide produce for Henry Flagler’s hotels in St. Augustine, Hastings has long been known as “Florida’s Potato Capital.” The town thrived for many years, but changes in transportation and agricultural markets caused it to decline. In 2017, due to large municipal debts and the high cost of utilities, residents voted to dissolve the town. Hastings then became part of unincorporated St. Johns County. They are only the second town in Florida history to voluntarily disincorporate.

Ted Newhall, Miss Potato Queen Susan Deen. 1962. State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory.

MAPPING HASTINGS, FLORIDA

NEWNANSVILLE, FLORIDA

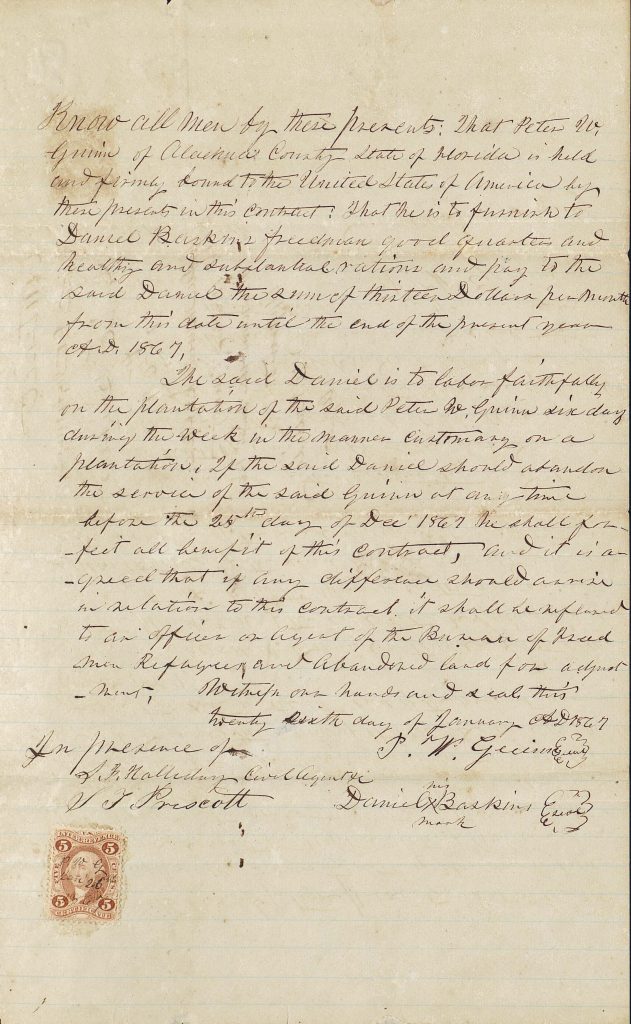

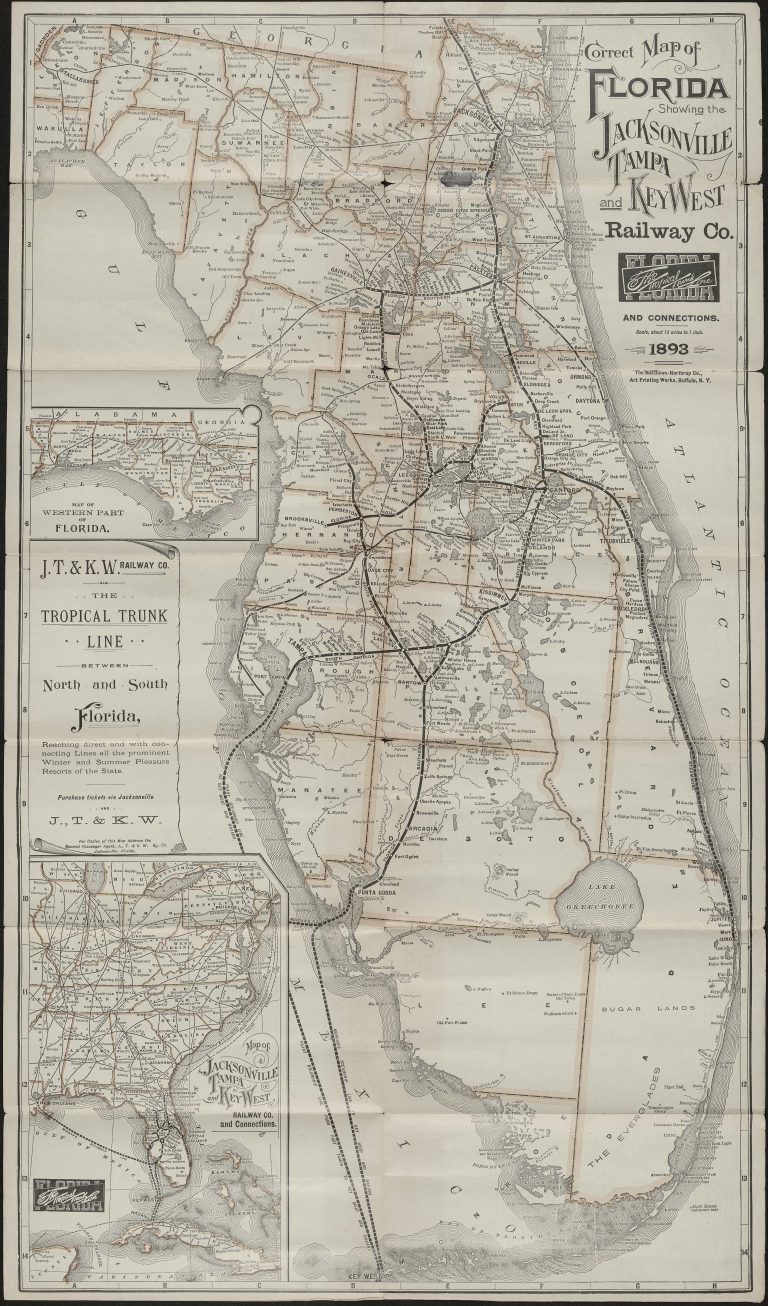

Established in 1828, Newnansville was the original government seat of Alachua County. Yet in 1854, the Florida Railroad Company bypassed the town. As a result, the Alachua County Commission voted to move the courthouse to Gainesville. Two more railroads went on to bypass Newnansville. The railroads’ slight, and the establishment of a new town called Alachua signaled the end for Newnansville. The entire town was eventually razed to the ground except for two cemeteries and a small portion of Bellamy Road.

MAPPING NEWNANSVILLE, FLORIDA

RELIGIOUS SETTLEMENTS

In 1823, Moses Elias Levy founded a Jewish utopia at Pilgrimage Plantation, near Micanopy (Alachua County). There he advocated for gender equality and a gradual emancipation of slavery. Five Jewish families settled on Levy’s land, but Pilgrimage Plantation burned down in 1835 during the Second Seminole War. There is no known record of their whereabouts after the fire.

In 1894 Cyrus Teed, known as “Koresh” built a “New Jerusalem” in the town of Estero (Lee County). The community began with two hundred settlers, but it gradually declined after Teed’s death in 1908. In 1961, the last four members donated most of their land to the State of Florida, which turned it into a state park.

MAPPING ESTERO, FLORIDA WHERE KORESH’S COMMUNITY ONCE STOOD

YAMATO

In 1905, Japanese farmers established the Yamato Colony in what is now Boca Raton. Yamato’s founder, Jo Sakai, wanted to introduce new crops and agricultural methods to the area. Sakai had trouble attracting families to Yamato so it never grew very large. They had plenty of competition for their main crop, pineapples, from Cuba and many of the settlers chose to sell their property during Florida’s 1920s land boom. In 1942, the US government seized the land and forcibly removed its Japanese-American owners. They built an Army Air Corp training base and destroyed the colony.

The last remaining member of Yamato, Sukeji “George” Morikami, donated his land to Palm Beach County in 1973. Morikami intended for it to become a park to preserve the memory of the Yamato Colony. Today it is the home of the Morikami Museum and Japanese Gardens.

Hoichi Kurisu (Japanese, 1939-), Morikami’s Memorial. 1999. Florida Ephemera Collection. Gift of Bess De Farber.

The Yamato Colony: Japanese Pioneers in Florida, Morikami Museum and Japanese Gardens. 2009. E 184 .J3 M67 2009. Library West General Collection.

MAPPING YAMATO, FLORIDA

FLORIDA INDUSTRIES

Many towns grew in support of new industries in Florida. Some of these naturally expanded along with the companies that spurred their development, while others were intentionally built in support of their industries. Phosphate company towns, such as Brewster, are now gone due to market fluctuations and environmental concerns. Natural disasters like the freeze of 1894-1895 caused the decline of Kerr City, which relied on citrus farming.

MAPPING BREWSTER, FLORIDA

MAPPING KERR CITY, FLORIDA

AFRICAN AMERICAN COMMUNITIES

After the Civil War, many African Americans formed their own communities. While Black towns faced the same social and economic pressures as other places, systemic racism often led to their destruction.

Established in 1891, Goldsboro was one of the earliest incorporated African American towns. Goldsboro’s incorporation meant that neighboring Sanford could not expand. But in 1911, Forrest Lake, former mayor of Sanford and a Florida state representative, pushed through a bill that dissolved Goldsboro’s charter and forcibly annexed it into Sanford.

Map of Goldsboro, Orange County, Florida. 1891. Goldsboro Collection. RICHES of Central Florida.

William C. “Hank” Young (American, 1966-), Rosewood Historic Marker. 2021.

In 1923, a white woman from Sumner claimed that a Black man, from the African American town of Rosewood, attacked her. An angry white mob descended on Rosewood and burned the town, killing at least seven people. Today, the Rosewood historic marker shown above acts as a roadside shrine.

MAPPING SANFORD, FLORIDA WHERE GOLDSBORO ONCE STOOD

MAPPING ROSEWOOD, FLORIDA

MAPPING SANTOS, FLORIDA

HURRICANES

On September 16, 1928 one of Florida’s worst hurricanes struck Palm Beach County. Heavy rains led to flooding and levee failures around Lake Okeechobee. This caused an estimated 2,500 deaths, most of which were African American farmworkers. Although the hurricane devastated Pahokee, Canal Point, Belle Glade, and South Bay, they were able to rebuild. West of Belle Glade, the town of Chosen was permanently destroyed. Communities on Torry, Kraemer, and Ritta Islands were removed to build new flood control structures.

Don Morris, The 1928 Hurricane in Florida: 112 Amazing Pictures Showing Scenes during and Immediately after the Storm… 1928. Palm Beach Press. F551.55 N714.

RAILROADS

Railroads were an economic powerhouse in Florida during the 19th and 20th centuries. They connected cities and helped tourism grow. Many rail lines supported agriculture, timber, phosphate mining, and other industries, creating hubs of activity in rural areas. When industries declined, trains left as well. As highways and airlines grew, the importance of railroads shrank. By the 1960s, railroads in Florida were mainly used to move freight or industrial products. Many of the communities that the railroads sustained faded away.

FINDING LOST COMMUNITIES

There are many ways to find lost communities. They can be as involved as going through county land records or as simple as driving through back roads and looking for road signs. Books on local history, historic maps, post office records, and other documents can provide the location of these places, while visiting in person can reveal the fate of the community.

FOLLOW THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA LIBRARIES ON SOCIAL MEDIA